***

On Your Marks…

You’re at the starting gate with your guest, and the time has finally come to do the interview. (For the previous installments begin here and then follow the links at the end of each installment.) I don’t pre-interview, because I want a sense of spontaneity during our time together.

Get Set….

There are a few things, however, that I remind my guests of before we begin. First, because it will be an edited interview for later broadcast, I remind them that they can stop if they need to repeat or correct themselves. I just ask them to start their sentence over from the beginning, so that it will be easier to make edits. If we are on the phone, I ask again to make sure that they are not on speaker phone. I also do a voice level check by having them spell their names slowly, asking them to speak louder or softer accordingly, as I adjust my recording equipment. (Once you have set the volume control on your recorder, don’t touch that dial!) As I’ve indicated previously, I check to see how the guest would like to be addressed. Most people are fine with being called by their first name, and that is certainly what is most comfortable for me.

When I’m interviewing guests whose ideas I may take issue with, I say nicely that I hope they don’t mind if at some points I challenge some of their ideas; I try to put it in a friendly, non-threatening way. Finally, I tell the guest I am beginning as I am about to start the recording, and say that after the short introduction he or she should feel free to respond.

There is, of course, nervousness and the whole matter of ego to deal with—both mine and the guest’s. While my interview aesthetic is not to be some faceless interviewer, on the other hand, I don’t want to be obnoxiously intrusive. As I have become more experienced, I find myself more able, somewhat paradoxically, to allow myself to stay more in the background. The ideal for me, and I think the most interesting for the listener, is for there to be an intelligent conversation between two intelligent people; but the focus has to be on the guest, not the interviewer. The interviewer’s main job, in my opinion, is to create the conditions that permit the guest to speak as interestingly as possible. I find that if I keep that goal in mind, the ego issue on my side tends to lessen.

Go!

How the conversation goes depends a lot upon the personality of the guest. Of course, you will have your interview outline in front of you. (I bold it, and print it in large 14-16 pt font, because I want to be able to scan it without fumbling.) You will soon get a feel for the guest’s speaking and conversation style. It’s like Goldilocks and the Three Bears: there will be the guest who speaks too slowly, the one who speaks too much and too fast, and the one who is just right.

The slow talker, immortalized by Bob and Ray, has thoughts and speech… which… come… at… an … agonizingly… slow… pace. As an interviewer, you are just dying to jump in and finish the sentence for the guest, but you need to have patience. Fortunately, you will be able to tighten up all those pauses when you get into the editing room. Also, those long pauses do give you a chance to re-direct the line of questioning onto topics which the guest may feel more more excited or passionate about.

The other side of the coin is the guest who talks very quickly, with barely a break for a breath. In those cases it can be very difficult to get in to ask the next question. If the guest is focused and articulate, for the most part, I do let the guest speak for a while, trusting again that in the editing room I will be able to trim back to the essentials. But still, you have to assertively find the places to jump in and get your questions asked, or the whole interview will go by, and you won’t get to ask your most important questions. It can be challenging.

For me, though, the most difficult problem is with guests who have a set script—either internally or written—from which they will not budge. No matter what questions you ask, they twist the question into the scripted response. Some guests will do it charmingly, some will do it not so charmingly. It’s kind of like a train going down a track that can’t be diverted. As an interviewer, I want to get beyond those kinds of scripted answers. That’s why it’s important here to grab an opportunity to ask one of your more unusual or personal questions. You want to gently knock the guest off course, to give them a little signal, that no, this isn’t just about formally reciting a press release, this is an actual conversation with someone who genuinely wants to know about you. Sometimes this will get them to loosen up and actually engage with you.

When the chemistry is right between you, however, and the guest wants to have a good conversation, it’s a pleasure. It may take a little while to warm up, but as the interview goes along, many guests, if made comfortable, will loosen up and play ball if they sense you have done your homework. You have to be a little careful, however, of the guests who get too familiar—sometimes when you ask them what they think of such and such, they will craftily evade by turning the tables and asking you what you think of such and such. It’s important to resist temptation. I generally reply with a quick answer of my own position, but follow up with, “But this interview is about you, not me. What do you think of such and such…” and continue from there. After the interview, I edit out my reply.

You Must Make The Path

All through the interview I am scanning my interview outline, and I am mentally checking off which questions have already been answered by my guest, even if I haven’t asked them. This means that you are actually listening to your guest. Nothing worse than being a Komodo Dragon Interviewer, as per the great Bob and Ray again. If a guest has already answered a question that I had planned to ask, that’s fine. I fill in with questions on my outline around that and continue making the path.

At times, a guest will start speaking early on about something I had planned to ask about much later. If I sense that that will take us in a direction which will make it hard for me to return to my earlier planned questions, then I ask the guest to hold off a moment with that thought, re-direct them to the general order of questions I had planned, and return to that thought later.

If you are really listening and really curious about what your guest has to say, then it’s only natural that a guest’s response could well prompt another question from you. I don’t think you should jump in with every thought you have, but as a representative of the listening audience, you should ask clarifying questions when a response doesn’t seem clear, and you should not be afraid to ask the follow-up questions which you think your listeners would ask themselves or like answered. Sometimes the most powerful question you can ask is a simple “Could you say more about that?” The unplanned turn off the road can be fruitful. But do find a way back.

The goal again is to make it seems as if it’s a natural conversation with one question leading into the next, all the while directing the interview into the general shape that you had outlined.

Take A Penny, Leave A Penny

After doing this for a while, I began to appreciate how interesting, difficult, and artful interviewing can be. After you try it for a while, you’ll never again listen to interviewers in the same way. You will begin to pick out models for yourself, interviewers whose aesthetic sounds right to you, interviewers of whom you’ll say to yourself, that’s what I want to achieve. Steal from them, imitate them, and then make your own path.

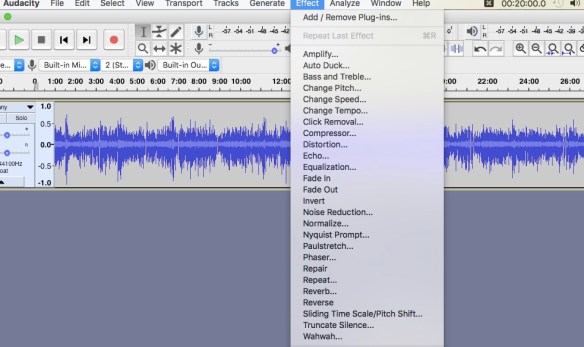

Next week, we’ll talk about beginning to edit the raw audio that you’ve just created.

Read the next installment here:

Radio Interview Production Workshop #8: Dept. Of Ed(iting)

Like this:

Like Loading...

***

***